One other debate in the Commons

during this session must be referred to, if it be

only to mark the wide interval which separates the

Liberal Party of the present day from the Whig

leaders at the beginning of the reign. On February 15

Mr. Grote brought forward his annual motion in favour of the Ballot in Parliamentary elections.

Hitherto little interest had been attached to the

project, owing to the disfavour with which it was

regarded by all but extreme Radicals. On this

occasion, however, several Ministers and many

supporters of the Government were known to have

pledged themselves at the polls to the principle of

secret voting. Lord John Russell had declared that

to carry such a measure would be tantamount to a

repeal of the Reform Act of 1832 ; that for the

Government to promote it would be a breach of faith

to those who had supported the extension of the

franchise, and he refused to be any party to " what

neither his sense of prudence nor of honour would

justify."

Sir Robert Peel supported the Government

in resisting the motion, and it was rejected by a

majority of 117 in a House of 513 Members. This was

hailed as a moral victory by the supporters of the

Ballot. Brougham was jubilant, and told the Lords

they must make up their minds to this fresh reform.

A few days later he declared in Greville's room that

it would become law in five years from that time,

and many people regarded it as paving the way to

Republican government. On the other hand Greville

quotes Charles Villiers, " one of the Radicals with

whom I sometimes converse," as declaring that it

would prove a Conservative measure, and that better

men would be chosen. In effect, it took, not five

years, but thirty-four, to reconcile Englishmen to

the practice of secret voting ; and Mr. Villiers has

lived to see that the protection thereby afforded to

the voter has certainly not operated to the

exclusion of Conservatives from office. But it would

be unphilosophic to argue that what was conceded in

1872 to an experienced and educated electorate,

without evil consequences, might have been bestowed

with equal safety in 1838, only five years after the

great measure of enfranchisement.

THE RIGHT HON. CHARLES PELHAM

VILLIERS.

Born

1802. Is a grandson of the First Earl of

Clarendon, and has represented Wolverhampton in

Parliament continuously from 1835 to the present

day. He took part, with Cobden and Bright, in the

Free Trade movement, and in the passing of the

Ballot Act. He and Mr. Gladstone are the only

survivors of those who sat in QueenVictoria's first

Parliament.

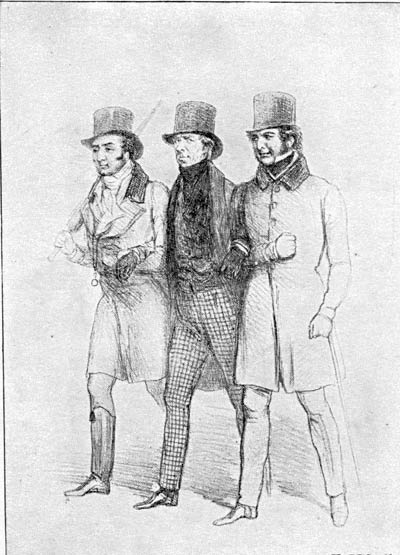

THE THREE SINGLES.

Lord Brougham in 1837 had opposed the Government

measures relating to Canada. For some time he stood

alone, and it was not until the Bill for Abolishing

the Canadian Legislature had made considerable progress

that he found himself supported by the

Earl of Mansfield and Lord Ellenborough. But though

acting together on this occasion, each had his own

separate motive and argument, and perhaps there were

not three members of the House of Peers who better

deserved to be acting singly and without party

connection. Lord Brougham is here represented with

the Earl of Mansfield on his right arm and Lord

Ellenborough on his left.