|

A Shameful

Episode

Before following the fortunes of

the Administration formed by Sir Robert Peel,

reference must be made to mournful news which, while

people at home were crowding round the hustings and

polling booths, were slowly approaching this country

from Central Asia. The most serious reverse to

British policy and the greatest disaster to British

arms which have happened in the present century were

the outcome of events which may thus briefly be

recapitulated. In 1837 Captain Alexander Burnes,

Orientalist and traveller, arrived as British agent

at Cabul, capital of the province of that name, in

the north of Afghanistan. The Prince of that

fragment of the ancient empire of Ahmed Shah was

Dost Mahomed Khan, n usurper, it is true, but a

popular hero, a soldier of remarkable ability, and a

sagacious and bold ruler. Dost professed the

friendliest feelings towards England, but, for some

reasons now unknown, was profoundly distrusted by

the Foreign Office. Captain Burnes thoroughly

trusted Dost, but his repeated assurance failed to

convince his employers that in his disputes with

neighbouring States, Dost greatly preferred relying

on English influence to accepting the advances

continually made to him by Russia and Persia. Burnes

was instructed to regard Dost as dangerously

treacherous, and at last Lord Auckland,

Governor-General of India, made a treaty with

Runjeet Singh, hostile to Dost, and with the purpose

of restoring Shah Soojahool-Moolk, whom Dost had

deposed from the throne of Cabul. A British force

invaded Cabul, overthrew

the brave Dost, and enthroned 'Soojah, whom nobody

wanted. But Dost Mahomed was a foe of no ordinary

mettle. On November 2, 1840, he encountered the

allied force of the English and Shah Soojah at

Purwandurrah and if he did not actually win the

battle, the gallantry of his Afghan cavalry caused

it to be drawn. Dost, however, was too wise to

believe that he could resist for long the force of

England. On the evening after the battle he rode

into his enemy's camp and placed his sword in the

hand of Sir W. Macnaghten, the British Envoy at

Soojah's Court. Dost was honourably treated, his

sword was returned to him, he was sent to India and

provided with a residence and pension.

But Dost was the darling of his

people. They hated Soojah, whom the English had

forced on them, and they rose in revolt against him.

Burnes was the earliest victim, for although, in

truth, he had all along stood stoutly for Dost, the

insurgents believed him to have betrayed their

ruler. He and his brother and all their party, man,

woman, and child, were hacked to pieces. Akbar Khan,

second and favourite son of Dost Mahomed, now put

himself at the head of the insurrection, and the

shameful part of the story began. Hitherto, there

had been blunders enough in English dealings with

this brave people : but there is nothing to blush

for in blunders provided they are clear of disgrace

; one cannot, however, ignore the truth that, after

a few weeks' fighting, British troops, having been

repeatedly beaten, became so demoralised that their

officers could not get them to stand before the

fierce Afghans. General Elphinstone, the chief in

command, was an experienced, able soldier ; but his

health had broken down before the insurrection

began, and he had written to the Governor-General

begging to be relieved of his command, which he felt

he was physically unfit to continue. Unfortunately

there was some delay in appointing his successor,

and the trouble came before Elphinstone could be

relieved. Against the personal courage of Brigadier

Shelton, the second in command, no reflections have

ever been made, but he proved lamentably supine at

moments when prompt action was most required.

Affairs went from bad to worse with the British

force in cantonments outside Cabul, until at last

Elphinstone, grievously weakened by disease, could

be brought to contemplate no course but abject

surrender. Abject surrender ! Not quite

unconditional, it is true, but on most humiliating

terms, including the release of Dost Mahomed and the

immediate evacuation of Cabul by the British.

Bad as this was there was darker

disgrace to come. The evacuation was delayed—on the

part of the British from a foolish " Micawber " hope

that " something would turn up "—on the part of the

Afghans, no doubt, in order that the advent of

winter should make the passes impracticable.

Macnaghten, the British Envoy, seems to have been

infected by the prevailing demoralisation, and fell

into a trap prepared for him by Akbar Khan. At the

very moment when he (Macnaghten) was negotiating

openly with the chiefs in Cabul he entered into a

conspiracy with Akbar to destroy them, to establish

Shah Soojah as nominal monarch, and to secure the

appointment of Akbar as Vizier. Macnaghten's

punishment made no long tarrying, for Akbar was

acting a subtle part. Macnaghten, accompanied by-

three officers, rode out one morning to a conference

with Akbar on the west bank of the Cabul river. It

was a solitary place, a befitted the discussion of

the contemplated treachery, but they had not been

conferring long before they were surrounded by a

crowd of armed country people. The British officers

remonstrated with Akbar ; at that moment Macnaghten

and his companions were seized from behind; a

scuffle took place; Akbar drew a pistol, a gift from

the Envoy himself, and shot him in the body.

Macnaghten fell from his horse and was instantly

hewn in pieces ; Captain Trevor was killed also, and

the other two officers, Mackenzie and Laurence, were

carried off to the town.

Deeper and deeper grows the

horror--more profound the shame—as the story

proceeds. General Elphinstone and Brigadier Shelton

lay in their cantonments with 4,500 fighting men,

with guns, and camp followers to the number of

12,000. Macnaghten's bloody remains were dragged in

triumph through the streets of Cabul, yet not an arm

was raised to avenge him. Major Eldred Pottinger was

for cutting their way out and dying on the

field, but no one would listen to him : negotiations

were opened with Akbar Khan, and the British force

were allowed to march out, leaving all their guns

except six, all their treasure and six officers as

hostages. They started, upwards of 16,000 souls, to

march through the stupendous defiles to Jellalabad

in the very depth of winter. Akbar Khan's

safe-conduct proved the shadow of a shade; either he

would not, or, as seems to have been the case, he

could not, protect them from hordes of fanatic

Ghilzies, who hovered along the route—shooting,

stabbing, mutilating the wretched fugitives. Akbar,

indeed rode with Elphinstone, and probably it was

true, as he declared, that he could do nothing with

his handful of horse to keep off the infuriated

hillmen. At last it became evident that a choice

must be made of a few who might be saved either from

a bloody death or from perishing of cold in the snow

and searching wind. Akbar proposed to take all the

women and children into his own custody and convey

them to Peshawur. The awful nature of the dilemma

may be imagined when such a proposal was agreed to.

Lady Macnaghten was placed in charge of the assassin

of her husband: with her went Lady Sale, Mrs.

Trevor, and eight other Englishwomen ; and, as an

extreme favour, a few married men were allowed to

accompany their wives. General Elphinstone and two

other officers were also taken as hostages. The rest

struggled on as far as the Jugdulluck Pass. Then

came the end: the hillsides were crowded with fierce

mountaineers ; the 44th Regiment were ordered to the

front ; they mutinied and threatened to shoot their

officers, broke their ranks, and were cut down in

detail by the Afghans. A general massacre followed.

Out of more than 16,000 souls who marched out of

Cabul a sorry score of fugitives were all that left

that horrible defile alive. Sixteen miles from

Jellalabad, only six remained: still the murdering

knife was plied, until, at last, one solitary

haggard man, Dr. Brydon, rode into Jellalabad to

tell of the literal annihilation of the army of

Cabul, and announce to General Sale, commanding in

that place, that his wife was in the hands of Akbar

Khan.

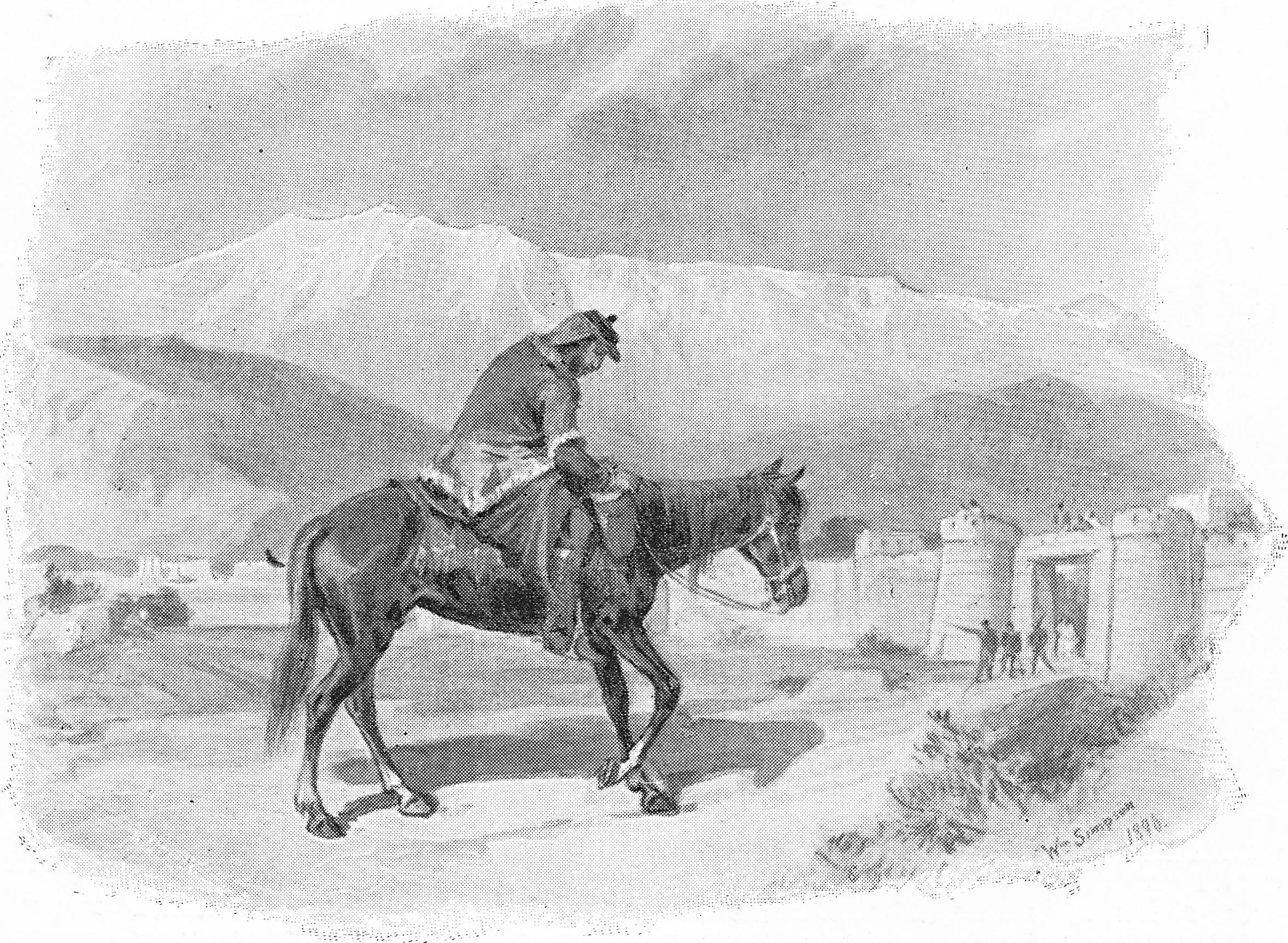

Annihilation of the British Force.

[From Sketches obtained on the spot.]

The gate shown is the Cabul Gate of Jellalabad. It

was from the top of that gate that the sentry on

duty first caught sight of the solitary figure, clad

in sheepskin coat and riding a bay pony, lean,

hungry, and tired, who alone survived the massacres

in the Huft Kothal and Jugdulluck Passes. Dr.

Brydon's form was bent from weakness, and he was so

worn out with fatigue that he could scarcely cling

to the saddle. The snow-covered mountain in the

background is the Ram Koonde.

Site Copyright Worldwide 2010. Text and

poetry written by

Sir Hubert Maxwell is not to be reproduced without

express Permission.

|